Building Resilient, Fault-Tolerant Supply Chains

By Ron Keith, SCRG

Originally posted on TTI MarketEye Blog

The shaking lasted for six long minutes, destroying everything in the restaurant and leaving the building itself leaning to the east at a precarious angle.

The earth had barely stopped shaking when Katsuko heard another roar, this one a bit higher in pitch and growing ominously louder by the second. It was the sound of a 40-meter-high tsunami crashing ashore some ten miles away.

What Katsuko survived that day was the most expensive natural disaster in world history. The higashi nihon daishinsai (Great East Japan Earthquake) is now known by the rest of the world by the name of the Japanese prefecture where the disaster took place, Fukushima.

The toll of the disaster was immense: 18,000 dead; 1.1 million buildings damaged, including some 120,000 that simply disappeared into the ocean; 9,000 factories out of commission and a total economic toll $235 billion, according to the World Bank.

Prior to the spread of COVID-19 in China and east Asia in early 2020, Fukushima was the single largest technology supply chain disruption event in more than 50 years. The global semiconductor industry was particularly hard hit by the earthquake, with top suppliers of silicon wafers and BT resin – key raw materials for semiconductor production – experiencing significant damage and production stoppage.

In the aftermath of Fukushima, “supply chain resilience” became a very popular term, with many companies taking significant action to build more resilience into their supply chains. But far more companies took little to no action to make their supply chains more robust, and thus experienced significant economic damage in the wake of COVID-induced production outages in China which quickly spread through most of East and Southeast Asia.

Many people have asked me lately why more companies don’t take action to diversify their supply chain or otherwise take action to reduce their supply chain risk. The answers I generally give depend on who is asking the question – and, of course, why. But in general, I tend to group the obstacles or impediments to companies building more robust, fault-tolerant supply chains into five primary reasons.

1) Excessive Focus on Supply Chain Efficiency

The design of a supply chain is perhaps the most important factor in its ability to withstand various shocks and continue to perform at normal or near-normal levels.

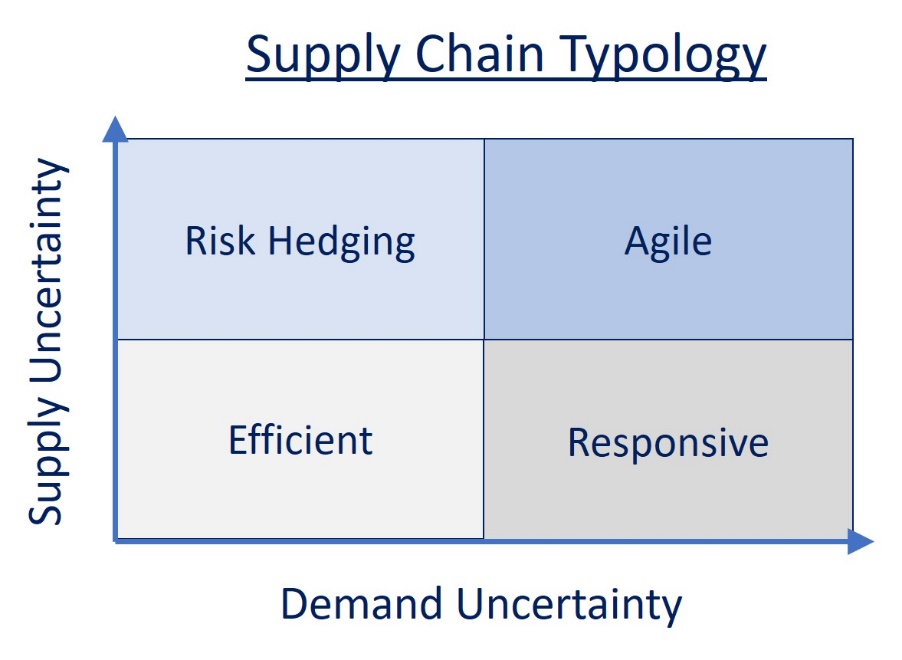

Stanford professor Hau Lee developed a typology of supply chains based on uncertainty (Lee 2002). Although Lee’s work was not intended to primarily address exogenous shocks to the supply chain, his work is nonetheless informative in that context. His supply chain typology, shown below in Figure 2, suggests that higher levels of supply uncertainty require a supply chain design focused on either risk hedging or agility. Events like Fukushima and COVID-19 create supply uncertainty which highly-efficient supply chains are not well positioned to react to.

Figure 2. Supply chain typology from Lee (2002)

Most of the primary tools and methodologies used for making supply chains more robust inherently add to per-unit cost, working counter to the main tenet of efficiency. Dual/multiple sourcing, strategic inventory buffers, make and buy strategies, manufacturing regionalization – all of these strategies add both cost and benefit to operating the supply chain. But the simple fact is that the leanest, most efficient supply chains (which is what 95 percent of my clients ask me about creating) are fundamentally not very resilient.

2. Uncertainty About the Probability of a Disruptive Event

Although several major events over the past decade created significant exogenous shocks to the technology supply chain, predicting such events is virtually impossible. Rather than guessing about timing, most companies assign a probability of a disruptive event occurring in a given year. But the list of possible events is long and varied, and few supply chain organizations employ statisticians or actuaries; determining what probability to use is challenging and it is impossible to determine what level of prevention spending is warranted.

3. Uncertainty About the Impact of a Disruptive Event

Even if the probability or timing of a supply chain shock could be known with some level of certainty, it’s extraordinarily difficult to accurately forecast the impact of a significant, broadly disruptive event such as COVID-19 that impacts a wide swath of the supply chain.

Taking the proper steps to build robustness and fault tolerance into a supply chain involves costs that can be quite significant. To know whether this investment makes sense and provides some level of return requires an understanding of the financial impact that these investments are intended to mitigate.

Some exogenous events create partial disruptions that can be dealt with after the fact by throwing money at the problem for overtime, premium freight or buying alternative materials at a higher price. But broader, system-wide shocks to a supply chain can cause devastating financial impacts, including a complete loss of revenue that results in an enduring loss of market share.

In the aftermath of Fukushima, 40 of Toyota’s tier-one suppliers went offline for some period of time, leading to the largest quarter-over-quarter revenue decline in the company’s history. The inability to keep dealers’ inventories at the desired level caused Toyota to lose market share to both Honda and GM.

4. Inability to Measure Resilience or Fault Tolerance

The most fundamental tenet of the science of management is that “You can’t manage it if you don’t measure it.” Although the concept of a more robust supply chain is understood by most practitioners, very few of them have any idea whatsoever how to go about measuring it.

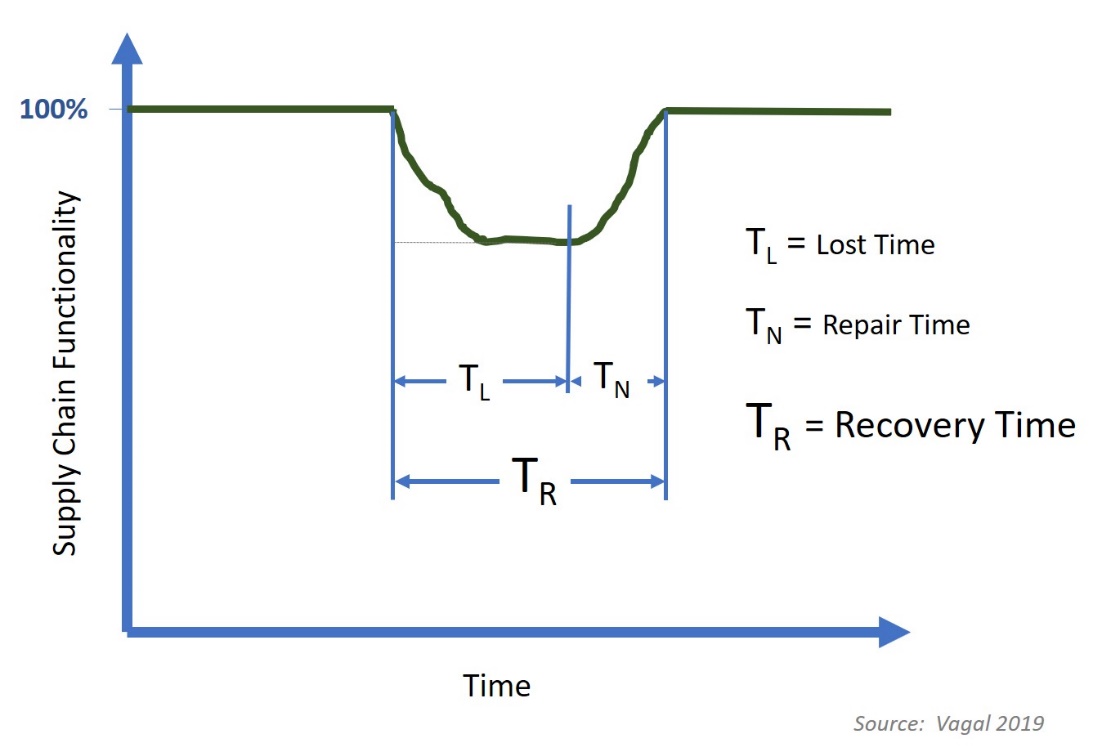

Most of the academic work around supply chain resilience focuses on complex network modeling to measure the resilience of different supply chain configurations. One key measure used for modeling is “Recovery Time,” or the total time from a disruptive event until the supply chain returns to normal functioning as measured by output. Some academics suggest that dividing the total lead time of the supply chain by the modeled recovery time provides a useful measure or index of a supply chain’s resilience.

Figure 3. Recovery Time as a measure of supply chain resilience

Given the extensive reach of modern supply chains and the complex interactions within them, modeling is a very useful tool for determining the robustness of various supply chain designs and disruption mitigation tools.

But the results of modeling, as valuable as they are, make for a key performance indicator (KPI) that is hard to operationalize in real time, and which is often viewed by supply chain team members as a bit esoteric. To overcome the limitations of modeling as an operational indicator, many companies have developed internal scoring methodologies that, rather than measuring supply chain resilience itself, measure the presence or absence of either risk factors or mitigation measures, as a proxy for supply chain resilience.

5. Misplaced Corporate Performance Measures and Incentives

Although it is difficult to measure actual supply chain resilience, there are a number of measures of a supply chain’s performance that are relatively easy to measure. Some of the most common measures include service level, on-time delivery, period-over-period cost reduction percentage, inventory turns, E&O percentage, premium freight spend and total number of suppliers.

All of these are important measures of either cost or performance, but none of these KPIs should be fully maximized or fully minimized if your company’s overall goals are financial in nature. Tying incentives to maximizing (or minimizing) any of these traditional KPIs almost always provides sub-optimal financial performance, and/or generally reduces the resilience of the overall supply chain.

Take Deliberate Action

Building resilience into your supply chain takes deliberate, targeted actions that are often at odds with the current operating metrics companies use to manage their supply chain performance. With very few exceptions, the primary tools available for building fault tolerance into supply chains involve investments that add some level of ongoing cost.

Calculating a return on these investments is difficult, and subject to a high degree of return uncertainty which generally makes it hard for supply chain professionals to justify the cost of these programs. But the catastrophic cost of massive supply chain disruptions such as COVID-19 is causing many tech companies to reconsider the need to spend a little extra to build a more resilient supply chain.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed in posts by contributors are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not imply an opinion of the officers or the representatives of TTI, Inc. or the TTI Family of Companies.