The Evolving Landscape of Counterfeit Part Mitigation

Each summer, just before the July Fourth holidays, the Center for Applied Life Cycle Engineering (CALCE) and the Surface Mount Technology Association (SMTA) hold the gold standard symposium, The Symposium on Counterfeit Parts and Materials, to discuss the latest in counterfeit electronic components and how to avoid them. Held at the University of Maryland just outside of D.C., it brings together experts from the mil/aero supply chain, test labs, university researchers, industry standards bodies and policy makers.

SOURCE: Kevin Sink, TTI MarketEye

One of the first presentations was from Richard Smith of the Electronic Resellers Association International (ERAI), detailing the number and types of counterfeits reported over the last year. In 2023, 786 counterfeit events were reported through ERAI, and while this number is up after the dramatic decline of the early COVID years, it is fully 30% lower than the peak in the early 2010s.

And after the MLCC allocation of 2018-2019, passives have fallen back down to their traditional low levels (0.5%). Once again, ICs are leading the pack, with analog ICs and microprocessors being the most counterfeited, but with memory on the upswing. Obsolescence still drives the market for counterfeits and the data mirrors it, with 46% of reports being for obsolete products, but the next largest category of parts counterfeited were in current production (33%) but with long lead times.

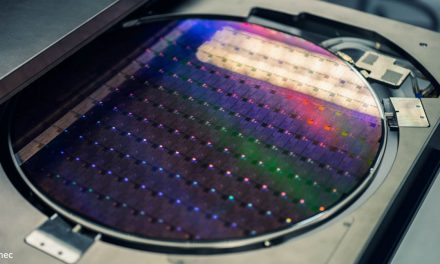

A throughline in many of the presentations was the impact of the 2022 CHIPS Act. While no one believes it will return the U.S. to semiconductor manufacturing dominance, there is recognition that it is a solid step in the right direction for national security. The souring relationship with China, the world’s reliance on TSMC in Taiwan and the astounding growth of AI exacerbate the need for self-reliance in cutting edge ICs for the West’s security. Several of the presentations laid out the evolution of the U.S. government’s strategy and the expected impact of the CHIPS Act.

Along this vein, I was honored to moderate the session on policy, both the from the U.S. government’s approach, and that of litigation over counterfeiting. In this session, the keynote presentation for day 2 was by Dr. Michael Fritze, of the Potomac Institute of Policy Studies: Microelectronics Acquisition Policy of the U.S. Government.

As Dr. Fritze explained, the challenge for the Department of Defense is the need to access the “state-of-the-art” technology, but this technology is largely produced in foundries outside of the U.S. Today’s smallest IC architecture (read: state-of-the-art) is available only from Samsung or TSMC. And, TSMC has 58% market share producing chips for many of the leading brands around the world. This is a remarkable geographic concentration in a risky part of the world. Add to this that China consumes 50% of the world’s semiconductor production while the U.S. only consumes 25% and we have a situation where global companies want access to the huge market in China, but we also need to protect their IP for national security.

Not only is access to state-of-the-art technology critical, the discovery of western components in drones used by Russia in Ukraine and the recent explosion of all of Hezbollah’s pagers makes very real the need for secure supply chains for national defense. One of the U.S.’ strategies since 1990 is investment in a secure foundry. Evolving from an NSA facility through two outside companies, today Global Foundries is this foundry for the U.S.’ secure integrated circuits. But not only is the U.S.’ military needs at risk, so are our commercial needs.

The inability of the automotive industry to get chips for their vehicles resulted in a dearth of new vehicles that took years to recover. Enter the CHIPS Act, which incentivizes the production of new foundries in the United States. In it, $39B is dedicated to counter the considerably larger subsidy China gives to its industry. So far, Intel, TSMC, Samsung and Micron Technology are the largest beneficiaries. Investments have been made in twenty states most notably with new foundries in Arizona, Texas, New York and Oregon with 16 other states

The security is all the more important as counterfeits are evolving beyond the harvesting of old devices to the cloning of chips in brand new packages, making them hard to detect. Of course, with this cloning can also come the insertion of malicious code. Dr. Fritze concluded his presentation with the need for policy to move beyond lowest cost that meets capability to also include secure process for critical infrastructure needs.

The second part of this session was a presentation by Patricia Campbell, J.D., from the University of Maryland Carey School of Law entitled, “Debugging the Trademark Laws: Civil and Criminal Liability for Trafficking in Counterfeit Materials.” This was the presentation I looked forward to most. For all the risk of counterfeits in electronic components, legal action has been nominal. In fact, Campbell revealed that no civil action has been field by trademark owners of electronic components in the last 15 years and few criminal cases have been brought. Why?

Campbell explained that among the many reasons are the lack of jurisdiction over counterfeiters in other countries, limited economic recovery that outweighs the cost, concerns about the negative impact on stock value and misperceptions about the applicability of the “material alteration theory.” The last two were new to me. A Texas A&M study published in the September 2018 of the American Marketing Association’s Journal of Marketing showed that a company’s stock price takes a 5-month 15% hit when the company pursues trademark infringement lawsuits and takes another 6-month hit if they win. This was shocking. Instead of being rewarded for having a product other wish to counterfeit, they are punished for having a product that could be copied.

Next, Campbell explained the material alteration theory whereby resale of a trademarked item that is materially different from the product sold by the trademark owner may constitute infringement or counterfeiting. This would then include used parts sold as new, remarked parts, fake parts in genuine packaging or rejected goods. Unfortunately, because two district courts have held that it does apply in criminal cases, but the D.C. district court said otherwise, the resulting uncertainty had a chilling on prosecutions for counterfeiting.

To see more prosecution for electronics counterfeiting, Campbell concluded that we need more involvement by the manufacturers, a renewed priority by the Department of Justice, consistent application of the material alteration theory and perhaps specialized legislation such as we have with fasteners (Fastener Quality Act 15 USC § 5401) and the fraud involving aircraft or space vehicle parts (18 USC § 38).

So, the 2024 Symposium on Counterfeit Parts and Materials was true to its reputation as the best source for electronic component counterfeiting. In it we learned of the positive steps enabled by the Chips Act, the frustrations of prosecuting counterfeiters and the altogether critical need of the U.S. and its allies to secure cutting edge technologies for both national defense and fair economic viability. With so many evolving aspects, staying abreast of these trends is crucial.